1993

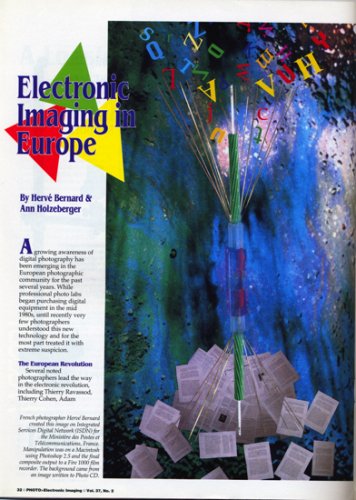

By Herve Bernard & Ann Holzeberger

A growing awareness of digital photography has been emerging in the European photographic community for the past several years. While professional photo labs began purchasing digital equipment in the mid 1980s, until recently very few photographers understood this new technology and for the most part treated it with extreme suspicion.

The European Revolution

Several noted photographers lead the way in the electronic revolution, including Thierry Ravassod, Thierry Cohen, Adam Wool fit, and Marc Garanger (who began working with videodisc and interactive technology in 1985). However, it wasn’t until the early 90s that the term « digital » began to surface at the large photo trade shows. In 1992, digitalization was the buzzword at Les Journees de l’Image Professionnelle (or JIP, a major European photo event). Not only had photographers lost their fear of the concept, digital photography was now the star of the show.

Since the last Photokina exposition in September 1992, the market has responded full force, by increasing the availability of new digital equipment and organizing educational seminars. Over 40 printers and several different photomontage (retouching) systems were exhibited during the international trade show in Cologne, Germany, thus confirming that this new technology had finally caught on in photographic circles. The Scitex booth, where the Leaf Digital Camera Back System was presented, was packed with people.

Concurrently, photo labs began to advertise their digital services in professional photographic trade journals throughout Europe. Approximately 20 percent of the French magazine Le Photographe deals with issues linked to digital photography and every two months a special issue is devoted to the subject. Since September 1993, the French magazine Chasseur d’Images, an amateur photo magazine, has included information on digital photography ; while Germany’s professional photo magazine Foto Wirtschaft (a Ringier Verlag publication) recently gave birth to a spin-off called Digital Imaging. Some have drawn parallels between this new market and the proliferation of mini-labs witnessed ten years ago, claiming that in two or three years the market will have matured- and shrunk-leaving only a dozen firms standing. By then, digital photography will have reached adulthood.

Professional Trends in Digital Imaging

While many European photographers still refuse to have any thing to do with digital photography, those that are making the transition are finding the simplest and most economical routes.

Subcontracting work to photo labs or pre-press houses is one option for photographers who cannot afford to invest in the equipment. German photographer Uwe Ommers, now based in Paris, works closely with the Dahinden Photo Lab.

Macintosh or IBM/PC compatible desktop systems are rapidly making their way into independent photo studios, as well as film scanners from companies like Agfa, Howtek, Sharp, Management Graphics, and Nikon.

Two years ago, Ravassod purchased a Rollei ScanPack for his Rollei 6000 series camera. Six months later, he added a small drum scanner, the Scanview 2500. He chose to make these major equipment investments because he lives in Lyon, where good scanning services are hard to find. Of his three Quadras, one, the 950, has a 1.2GB hard drive and 256MB RAM. He now controls a complete production system- which spans the original shoot, image manipulation, layout, and color separation.

Samovir Debosz, a German photographer, limited his investment to a Quante ! Graphic Paint Box and a Nikon EPIC (Electronic Picture Input Camera). He uses the EPIC to digitize old work or shoot new images (stilllifes for the most part, due to lengthy exposure time). And he turns to the Graphic Paint-Box to create backgrounds and assemble motifs.

Like many other photographers, Debosz subcontracts peripheral work, rather than investing in expensive input and output equipment. Thierry Cohen works this way as well, sending his work to Picto, a Parisian photo lab equipped with a Dainippon Screen 747 scanner and a Fire 1000 film recorder.

Marc Garanger is probably one of the few French photographers with significant expertise in the area of interactive digital presentations. One thousand copies of his videodisc Death Valley (digitized entirely from original photographs) have been sold in France. Voyager Company will act as distributor of Death Valley in the United States, as well as for Garanger’s second videodisc, Looking at Planet Earth, which has already sold 6,000 copies in France and the U.S. The second videodisc is made only with archived pictures. Like all major technological advancements, the digital revolution has forced people to learn new skills, to make choices and to adapt to changing expectations.

Photographers are being forced to reevaluate their professional roles, whether it be in photojournalism, industrial, or commercial photography, portraiture, fine-art photography, or related technical areas.

The photographic industry is undergoing an extraordinary period in time. Most photographers today learned to print black-and-white photographs by traditional methods. Now we are discovering an entirely new way of creating images. Such changes usually occur only once in a century. Although it may be difficult to follow the rapid pace of our evolving technology, we are lucky to be shaping its course.

A photographer’s identity is not limited to what he or she can do with silver. Digital photography should be seen as a new market opportunity not only in already established fields, such as photo-retouching, but in entirely new areas, such as multimedia.

About Hervé Bernard

Herve Bernard is a Paris-based free-lance digital photographer who writes regularly on the topic of electronic imaging in several European publications. He has exhibited widely in Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Republic of Czechoslovakia, and Belgium). Several of his photographs are in the permanent collections of the French Bibliotheque Nationale, Le Louvre, and the Musee Carnavalet, among others.

Bernard studied advertising, marketing, and photography as a student, and worked as a photo lab technician in the early 1980s. Eventually he took a job with France-Telecom to assist in the development of screen graphics for the Minitel system in France. Eventually he became involved in computer video, and later established his own business providing photo montage computer images to commercial clients throughout Europe.

Bernard photographs with a Sinar 4x5 view camera and Pentax and Canon 35mm SLRs. To create his photo montages, he works on a Sun SparcStation 1 OSX, using Graffiti software from Caldera Graphic.

About Carol Ann Holzeberger

Carol Ann Holzeberger is an American artist who, after a decade painting in oils, now works exclusively with digital media and creates interactive digital presentations.

About France-Telecom Minitel Communications System

The success of France’s Minitel System is unique in the electronic communication industry. Minitel is a small terminal with an 8.8-inch diagonal black-and-white screen, an alphanumeric keyboard, and some additional key functions-each unit is connected through the phone lines to a host computer. Minitels can be hooked up to television sets, and can come with a color screen. The computer graphic interface is very simple and fits in asquare 25 lines high and 40 characters long. Minitel can be found in homes as well as offices. In 1992, there were more than six million Minitels in France, a 16 percent increase over the preceding year.

Minitel’s first role was to replace phone books in French homes and businesses. The first three minutes of log-on time are free when accessing addresses or phone numbers. You can also use it to get movie and theater schedules, weather forecasts, or to make air or rail reservations. Through Minitel, you can have access to financial information about a given company (including the names of the shareholders, for example, or an indication on whether or not the company is making or losing money). You can also find out whether a given product has been patented (or if a patent exists without a product) ; you can learn where or how to find home work, and even type a draft of your resume which will be returned to you, by mail, corrected and printed on a laser printer.

France-Telecom began the service in 1981 as a local experiment, limited to a Parisian suburb. It was extended to all of France in 1982. At first, Minitels were handed out free to anyone who asked and already had a phone. Now you have to pay between 10 and 100 Francs (about 20 dollars) a month to rent one, depending on the model. When you use your Minitel, it’s charged on your phone bill. Part of the fee goes to FranceTelecom and part goes to the firm providing the particular service you connected to. Not only do prices vary according to the service, but individual companies earn less depending on the kind of service they offer. For example, a game might cost less to use than a database, and cost more in terms of percentage of income paid back to France-Telecom by the firm that provides the service. This doesn’t prevent game companies from being highly profitable. In 1992, Minitel enhanced its interface by allowing for the transmission of blackand- white photographs with 64 levels of gray on screens 320x240 pixels wide.

The transmission speed is 4,800 bits-per-second (bps). as opposed to the current baud rate of 1,200 bps from the host computer to the Minitel, and 75 bps from the Minitel to the host computer. Photo Minitel baud rate will eventually be boosted to 9,600 pps, heralding real multimedia services with sound plus still images. Test runs have so far featured snap shots and resumes of actors, industrial real estate views, shots of the tennis match at Roland-Garros, or information and help about Apple software.

Regard sur l’image

Regard sur l’image